The ISOL-MET Project is an initiative to explore how the case method can be creatively applied to teaching and developing soft skills in the classroom. Our basic case study narrative concern issues that arise in the contexts of ships, offices, and maritime communities. We have been researching, writing, and refining case studies on topics ranging from diversity and growth mindset to a controversy over what is a leader on the ship.

During the Chios Spring School, in April 3-10, we have experimented with many different methods of case teaching as there were case teachers. We tested methodologies for case-based teaching soft skills. We have concluded to several guidelines to produce a high-energy case-based class.

This article presents these basic guidelines for a case instructor. It is not intended to be a complete list of instructor duties but to provide helpful suggestions and a road map of a way to approach this teaching methodology.

1- Identifying a Case

After an instructor decides to utilize a case-based format, one must identify the type of cases to use. Good soft skills cases which relate to the content and learning outcomes of the course, are ones that engage students the most and develop skills. The cases chosen should be researched “real” cases – not fictional or library-based cases. Good cases are based on a real person facing a real problem and seeking a solution to that problem. The case is a puzzle that needs to be solved. It tells a story that involves conflicts or issues for a protagonist, someone to whom the students can relate.

The best cases are the ones with no “perfect” answer. A good case for teaching soft skills presents the personality, cultural, and social facts of the problem and requires students to grapple with the nuances of the situation. Either explicitly through role-playing, or implicitly through the questioning strategy of the instructor, the student’s lens for the case is the very complicated vantage point of an investigator.

A good teaching case encourages unraveling the dynamic interplay between the inductive and deductive methods of discovery. As decisions and maritime work environment issues become more complex and interdependent, it is important for students to learn to distinguish between a major or minor issue, separate problems from symptoms, make defensible decisions and provide evidence (from the case) to support them. It must be a case that reads somewhat like a good novel with an interesting problem with real people the students can identify with in some way.

2- Preparing the Case

Case preparation is more difficult and time consuming than reading a chapter in a textbook and working problems to use for illustrative purposes in class. The instructor must know the facts of the case (inside and out), identify the key issue(s), decide her/himself, and then perform analysis. Students will go through this same exercise, but the instructor has the difficult job of trying to determine what all the students may say.

The less you prepare, the more you will be tempted to direct the discussion. You must over-prepare to remedy your own apprehension about the need to provide a “right” answer. The challenge for the instructor is to give up their own “expertise” and allow the students to be in charge of their own learning. Good case preparation on the part of the instructor will determine the energy in the classroom, the enthusiasm of the students, the learning that will take place, and the flow and quality of analyses. Case teaching requires adhering to certain process techniques, such as, listening, logic, following (a student building on another’s comment), conciseness and evidence.

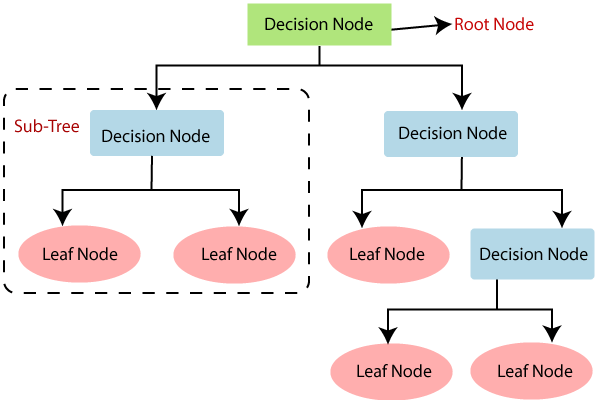

The best way to over-prepare is to develop a case map of questions that force students to make a difficult choice. Guidance can be achieved by developing a case map with good questions, doing a time plan, and constructing a board plan.

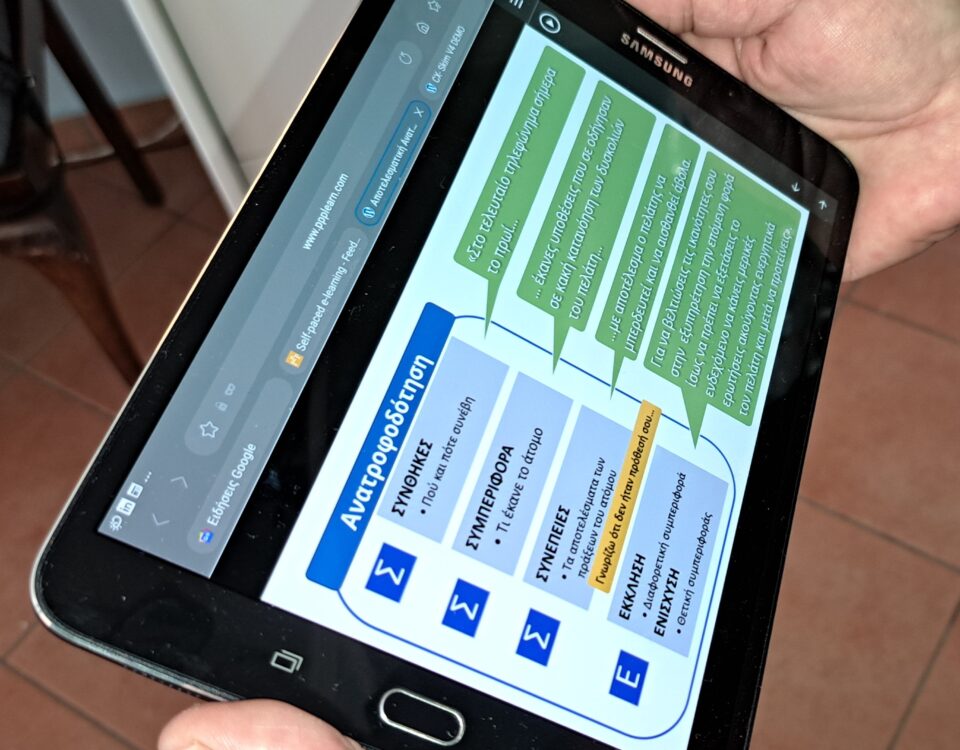

Case Mapping

Case teaching is a “question-oriented” approach, not a “solution-based” approach to teaching.

In the case map the instructor details a question strategy that enables students to discover for themselves the issue(s), arguments, and theories implicit in the case.

Develop a robust plan that details when you will introduce each major question that unwraps the dilemma. The benefit of case mapping is that you know the course flow every moment. If you know that and why the case was selected, you can prioritize which questions, tools and frameworks deserve extra time. Also, knowing where you are in the course flow helps if the discussion wanders off track.

Be certain to identify the overarching outcomes you want them to master with the case. From there you can begin to draw a “map” as to how you want them to reach that goal. As you strategize, you might think of this as mapping out your case. Keep in mind as you do that even though you may begin class with the exact same question, discussions frequently follow quite disparate paths as students articulate details or express ideas in divergent sequences. You need good open-ended questions. In the end, your goal is to bring both classes to the same set of themes and conclusions. This winding road to your class goals argues for mapping a case during your teaching preparation.

Mapping can be explicit or implicit. Formal mapping—projecting on paper the potential directions a case might take and drafting a question sequence—can be especially helpful for beginning, for case teachers. Detailed planning can help you create and manage a somewhat more orderly class plan and reduces your need to think on your feet during the case discussion.

Look for Role Plays

Are there any questions or issues where it would be helpful to assign two or more students to roles from the case and ask them to debate an issue? Phrase the first question in such a way as to encourage a debate based on evidence versus an exchange based on vague questions.

Create a Time Plan

On a separate piece of paper, break out your available class time into blocks of time, starting with your launch, followed by each of your anchor questions and ending with a student summary and your summary. Estimate the time and mark it in the margin.

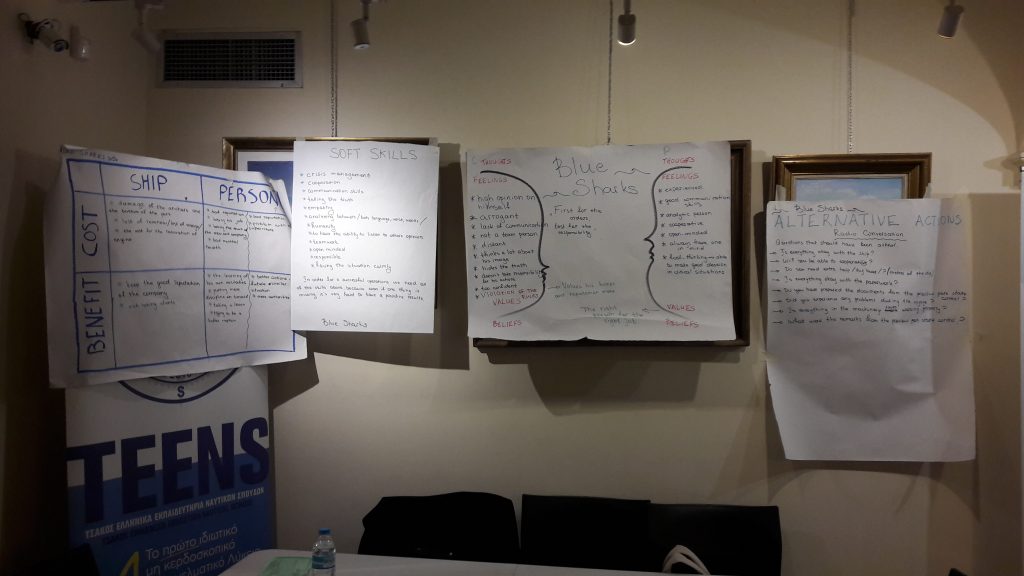

Construct a Board Plan

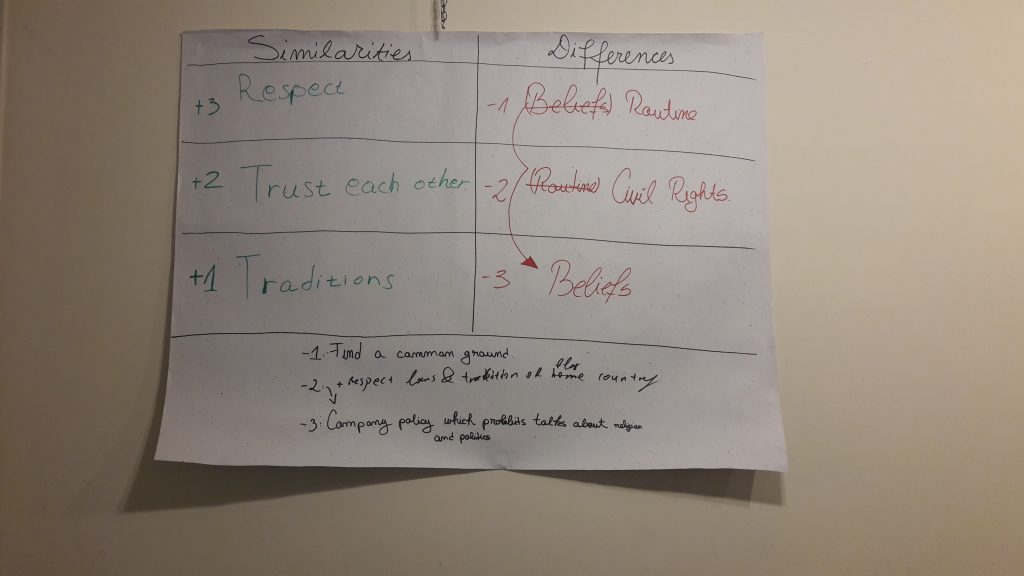

Sketch out a representation of the boards in the room. The goal is to depict how you would like the boards to look at the end (though not what you expect students to say).

Choose where you intend to capture the remarks of the opener and the class vote on the opening question. Choose where you will write the “pro/con” or “yes/no” for each debate you intend to provoke. Where will you capture any numerical analysis? Where will you write the student’s summary of “lessons learned?”

Strategic recording of class discussion can help students recognize that they can learn from each other, not just from the “sage on the stage.”

3- Running the Case

Once the case is under way, you want to concentrate on three things: “individual comments, group thinking, and your teaching plan.” A case discussion places you in a continuing cycle of questioning, listening, and responding.

Asking questions is key to executing your strategy for the session. Of course, your most immediate concern is to generate focused participation. This makes your first question critical.

When thinking about your questions, consider this observation from Albert Einstein: Most teachers waste their time by asking questions which are intended to discover what a pupil does not know, whereas the true art of questioning is its purpose to discover what the pupil knows or can know.

Questions

The Launch Question

Use a launch question that dramatically puts students in the shoes of the decision maker facing a harrowing dilemma. This question should put the students in the shoes of the protagonist (decision maker) that is facing a high stakes decision. Your goal is to create a controversy within the class. Occasionally, you may use the opening question to distract students from a more fundamental issue because you do not want them to jump to conclusions too soon.

Anchor Questions

In every class, you will have three to four questions that will anchor the discussion. Each of these questions should require the student to take a specific stand and encourage a lively debate. You branch off these questions into sub questions to have the students dig deeper into the learning objectives of the case.

Transition and Summary Questions

Once it seems students have exhausted an anchor question debate, you can summarize the key points made by both sides and transition to the next questions.

Then use questions to move students through the five typical stages of case analysis:

- What is the situation?

- What are the possibilities for action?

- What are the consequences of each?

- What action, then, should be taken?

- What general principles and concepts seem to follow from this analysis?

Also, use a summary question that raises even more fundamental issues and advances further the discussion.

Active Listening

Listening is most important—without effective listening, the process will be stopped after the first discussion question is thrown out to the class and quickly answered. Actively listening to student comments allows you to use follow-up questions to push individual or collective thinking. You can take advantage of opportunities to highlight important points or to shift the conversation to a new direction. Learning to be alert and receptive to student comments and questions throughout a class session will help you seek clarifications when a student comment is unclear, lead students to themes and assumptions that underlie a diverse series of comments and bring the session to a positive closure.

Validating Student Participation

One case teaching dilemma is the tension between validating responses and pushing students to think critically and to articulate difficult arguments. Case teaching is a collaborative enterprise: The safety of the collaborative experience encourages students to venture intellectually. Therefore, confrontational approaches could alienate students and be counterproductive. If some students appear to be intimidated, others in the class may sense that it is not safe to venture ideas or opinions. Just as building consensus can obscure a greater diversity of opinion, collective safety may come at the cost of critical thinking. You can validate and challenge students without sacrificing learning or taking casualties.

Separate the validation for participating in the process of collective discovery from the merit of the contribution’s content. This way you can signal students that venturing into the discussion—whether right or wrong—is valued. In a case class, students can get points for simply playing.

Using the Blackboard

Use the blackboard, overhead transparencies, or your computer as an assistant to record the conversation—track where you have been, direct the conversation to meet your class goals, suggest important notes for students to record, build discussion pathways, organize material, validate individual student comments. With the blackboard, you can stop and ask students to reorganize visually the recorded thoughts, imposing a structure on what may appear to be a chaotic stream of ideas.

Use the board as a tool to hold a good thought that you are not quite ready for the discussion. If the discussion needs to be redirected or to be summarized you can stop and say, “Let’s see what we’ve developed here on the board . . .”

To let ideas, bubble out rapidly and then take time to recap and reshape them, let students generate a “list” of answers or viewpoints, then go to the board and say, “Let’s try to summarize where we are in this case. This not only allows you to get the key points in written form but also signals students that, during the discussion, they need to be listening carefully to what their classmates are saying.

Strategic recording of class discussion can help students recognize that they can learn from each other, not just from the “sage on the stage.

Summary

To ensure that students leave class having learned the objectives you set, you will need to “debrief” them.

In case you choose to close the case study session you might return to your board space—or wherever you have kept track of the conversation— and highlight important points which connect specifics to general principles. At this point you can choose to move from the specific to the general, or vice versa. With this approach, you will likely do most of the talking during the last ten to fifteen minutes of the class. You have the opportunity to introduce the next session, explaining how this session has laid the groundwork for the next.

Another approach is to ask students to report out—as groups or as individuals— what they consider to be the summary and conclusion of the session. Or, you may ask them to take a few minutes and write down their thoughts. If you do the latter, since you want to be sure they get the lessons you have in mind, you should be sure to ask a specific question—or set of questions—designed to elicit the kind of information you seek.